|

德国picotweezers品牌,高分辨率三维单细胞单分子力学捕获分析光镊系统(3D Force Sensitive Optical Tweezers)

PicoTweezers是一种结合了光镊技术及微视图像计算集合的分子生物力学分析系统。PicoTweezers作为一个独立的系统,可以与蔡司Axiovert、AxioA1或D1显微镜联合使用。PicoTweezers配备了功率为1W或5W的红外光纤激光器,可达激光陷阱捕获力范围是400pN——2nN。PicoTweezers的3D-压电平台可以实现x轴和y轴为200μn;m的分辨率,在z轴方向可以实现20μn;m的分辨率。独特的视频分析系统(Video-analysis)可以达到至少2.5纳米的横向和轴向分辨率,其图像拍摄速率为200帧/秒,X、Y、Z互相成像速度为400赫兹,可对生物大分子进行0.1PN作用力分辨率的实时分析。

图1 PicoTweezers装配示意图

系统工作原理:

分子之间的作用力是在三维方向上分布的,所以为了计算大分子之间产生的各种作用力,需要在X、Y、Z三个维度上进行作用力的**检测,并且要求在这三个维度的测量空间比较大,以实现实验的自由度和多目的性。

PicoTweezers系统使用视频分析系统(右下图)作为粒子追踪、检测和力测量的系统,该系统虽然相对复杂,但模块化的配置和稳定的组装赋予了该系统易于使用的特征。

在测量的过程中,被光阱捕获的颗粒会在三个方向上对光进行阻挡,导致光线偏转,PicoTweezers的视频分析系统通过获取偏转的图像来分析作用力的变化,进而可以分析分子之间作用力的变化。由于该系统非常稳定,且不需要校准、没有试验和空间的限制,所以该系统应用领域非常广泛,是生物学、分子生物学、材料学研究者在大分子生物力学研究中的***实验仪器之一。

系统拥有自动、简单和可靠的力校准系统

该系统在三维空间中的力校准是通过斯托克斯阻力法移动3D-压电平台周边的介质来进行的。在具体的应用中,作用力的检测是通过基于视频的Allan方差分析和校准途径来实现的,其过程主要是通过对微小粒子的波动进行图像记录和分析,在此过程中,不需要施加任何摩擦力。在实验过程中,斯托克斯方法和Allan方差都不需要对光阱刚度k进行判定,即使需要,视频分析软件可以自动进行计算。

系统的计算原理

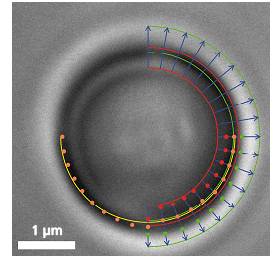

系统拥有两台高速数码照相机。**台照相机对光学阱捕获的粒子的周围区域进行成像,**台高速CMOS照相机对被放大的粒子大图像进行测量。相关的关键会实时分辨并锁定每个帧图像的边缘部分,确定出图像的灰阶和合适的范围,以此来确定或获取粒子的直径。

当外在的作用力施加在粒子上面时导致粒子在Z-轴上发生位移时,粒子的直径会发生变化,软件会将这种变化通过Z-轴的作用力表现出来。而粒子受到水平方向上的作用力时,仅仅改变图像的圆心的位置,但是其直径并不会改变。这样通过获取图像的位置的变化就可以分析粒子纳米级别的水平方向受到的作用力,进而分析出粒子在X、Y轴上所受到的作用力。

粒子在Z-轴上作用力会改变图像的直径,在X、Y轴上所受到的作用力会改变图像的圆心位置

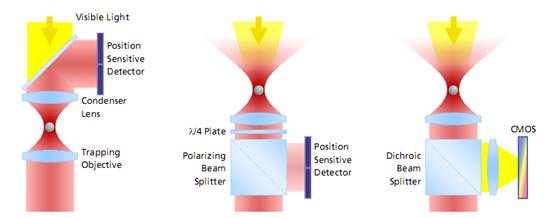

力测量的三种方式对比:

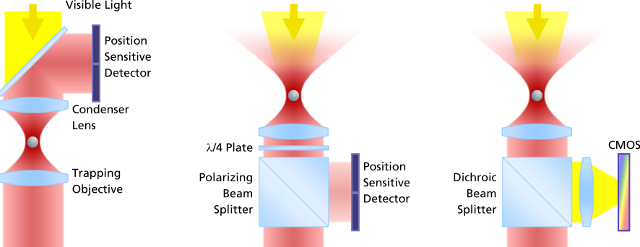

左边:是传统光镊的监测方法。激光通过捕获粒子,然后收集前向散射光并投射到探测器感应粒子的偏转。由于获取图像之前需要设置冷却器以进行**地调节,这种设置获取的图像容易漂移和错位,导致误差;

中间:从颗粒被捕获的目标收集背散射光,入射激光设置分光器并投射到检测器。这种方式测量的量程大,同样可以建立基于视频的检测方法,但**度不够。

右边:这是PicoTweezer的检测方法,同样也是通过设置并收集背散射光,然后通过分光器并投射到检测器。但是PicoTweezer系统采用了高灵敏度的CMOS图像传感器进行处理,并添加一组聚焦透镜进行图像聚焦,从而可以实现对纳米粒子图像的更**测定。其建立的基于图像的检测方法允许粒子更高的多样性,数据吞吐速度更快,分析效果更**。采用这种方法的优势之一是激光器和光阱之间的光学路径无需对检测器进行校准或调整,对于被监测的对象粒子的直径和移动可以被长期地监测而不会发生漂移。

图 光镊子测量分子力的三种方式对比

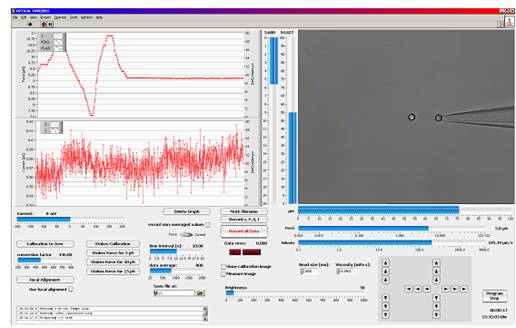

图PicoTweezers软件工作界面

仪器亮点

1)定量在三维方向实现0.1 PN分辨率下的3D测量

2)*大光阱捕获力可在1 W光纤激光器下达到400 PN

3)通过光镊实现对捕获对象精度为纳米级别的操控

4)拥有紧凑、超稳定模块化系统

5)可编程的LabVIEW?软件界面

6)不需要检测校准,软件计算非常容易

仪器应用范围

1.)单分子与活细胞的操控和分析

2)高分子弹性分析、微流控分析

3)分子相互作用、纳米孔分析

应用案例

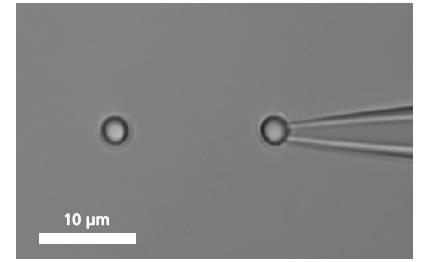

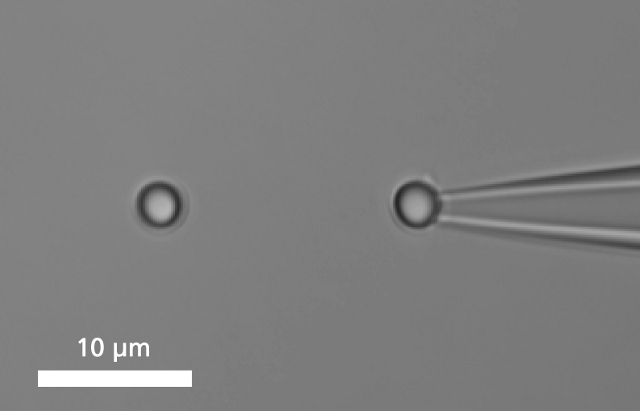

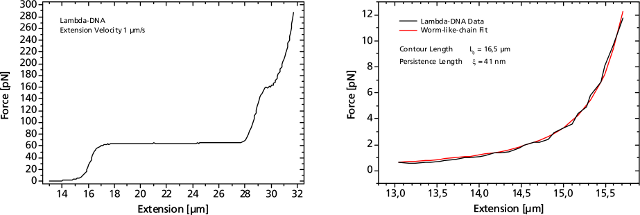

1)单分子的捕获及分析

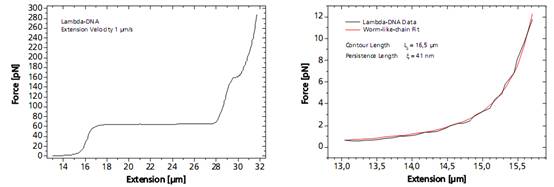

单个DNA链通过两端的官能基团固定在两个微珠之间。其中的一个微珠被玻璃微吸管固定,另外一个微珠被光镊俘获,通过移动压电平台增加珠之间的距离引起的受控DNA的机械张力。作为响应的分子的力 - 延伸曲线表现出DNA特定的机械性能,结果可以计算DNA的熵弹性,DNA的一个过渡延伸平台区和熔融过渡区域。

图DNA分子的捕获及分析图谱

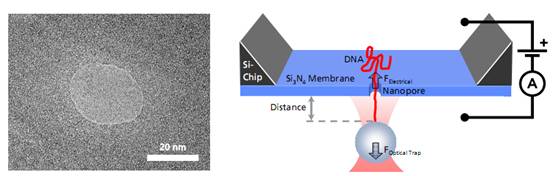

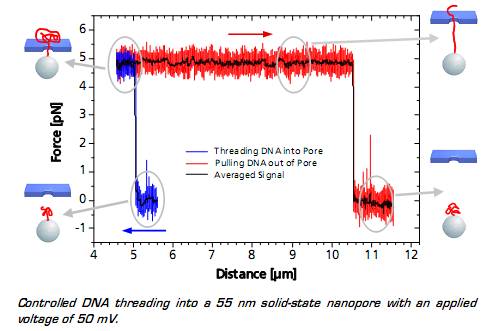

2)单个DNA链的易位过程分析

PicoTweezers可用于纳米孔分子生物学的研究,他们迅速演变成单分子检测领域一个非常新颖的技术。当单个DNA分子或DNA-蛋白复合物通过纳米孔时,这个过程可以被PicoTweezers监测并分析,相关数据可以确定DNA的易位动力学和DNA上结合的蛋白质的位置。

纳米孔测量的优势主要表现在:(1)可在非常低的浓度和很小的样品体积下测定目标分子;(2)可同时进行基因与生物标志物的筛选;(3)由于不需要进行放大及转化,分析测量的速度将很快且费用低廉。

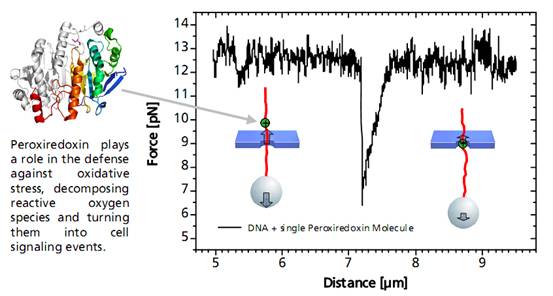

当捕获的的粒子上的DNA接近纳米孔(至5微米的距离)时,带负电荷的DNA通过DNA骨架的静电力立即进入纳米孔中,这种效果可以通过监测的力信号得到。可以看到这种作用力在到达一定稳定值后突然变化,显示出DNA的易位过程。系统所测得的力取决于施加的电压以及纳米孔的直径。当整个DNA链与纳米孔另外一端的距离为10.5微米时,表明DNA链被拉出孔,所述力降回到零。

目前PicoTweezers可结合各个实验室已构建的纳米尺度装置对单分子进行分析。包括生物纳米孔(通道) (由各类蛋白质分子镶崁在磷脂膜上组成)、固态纳米孔(通道)(包括各种硅基材料、SiNx、碳纳米管、石墨烯、玻璃纳米管等)及两类相结合的杂化纳米孔(通道)。

图 DNA的易位过程分析图谱

3)单个DNA结合蛋白分析

当结合到DNA链上的单个过氧氧化还原酶通过纳米孔过程中,会发生非对称的力的信号。这种信号可以作为蛋白质在DNA上的结合位点的无标记的定位信息。相关的力学信息结合DNA和蛋白质的特征,可以进一步得出其蛋白质与DNA的结合作用力来源于蛋白质与DNA骨架电荷的作用力。当单个DNA结合蛋白通过纳米孔时,DNA与结合蛋白之间的静电引力减少,有助于分子通过微孔。

图单个DNA结合蛋白分析图谱

参考文献

-

S. Knust, A. Spiering, H. Vieker, A. Beyer, A. G?lzh?user, K. T?nsing, A. Sischka and D. Anselmetti Video-Based and Interference-Free Axial Force Detection and Analysis for Optical Tweezers Review of Scientific Instruments, 83, 103704 (2012)

-

Spiering, S. Getfert, A. Sischka, P. Reimann and D. Anselmetti Nanopore Translocation Dynamics of a Single DNA-Bound Protein Nano Letters, 11, 2978 (2011)

-

Sischka, A. Spiering, M. Khaksar, M. Laxa, J. K?nig, K.J. Dietz and D. Anselmetti Dynamic Translocation of Ligand-Complexed DNA Through Solid-State Nanopores with Optical Tweezers Journal of Physics - Condensed Matter, 22, 454121 (2010)

-

Kleimann, A. Sischka, A. Spiering, K. T?nsing, N. Sewald, U. Diedrichsen and D. Anselmetti Binding Kinetics of Bisintercalator Triostin A with Optical Tweezers Force Mechanics Biophysical Journal, 97, 2780 (2009)

-

Pla, A. Sischka, F. Albericio, M. Alvarez, X. Fernandez-Busquets and D. Anselmetti Optical-Tweezers Study of Topoisomerase Inhibition Small, 5, 1269 (2009)

-

Sischka, C. Kleimann, W. Hachmann, M.M. Sch?fer, I. Seuffert, K. T?nsing and D. Anselmetti Single Beam Optical Tweezers Setup with Backscattered Light Detection for Three-Dimensional Measurements on DNA and Nanopores Review of Scientific Instruments, 79, 063702 (2008)

-

Anselmetti, N. Hansmeier, J. Kalinowski, J. Martini, T. Merkle, R. Palmisano, R. Ros, K. Schmied, A. Sischka and K. T?nsing Analysis of Subcellular Surface Structure, Function and Dynamics Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 387, 83 (2007)

-

Sischka, K. T?nsing, R. Eckel, S.D. Wilking, N. Sewald, R. Ros and D. Anselmetti Molecular Mechanisms and Kinetics between DNA and DNA Binding Ligands Biophysical Journal, 88, 404 (2005)

|

英文介绍Introduction

Our Optical Tweezers System Provides:

-

Quantitative 3D Force Measurements with 0.1 pN Resolution

-

Achievable Trapping Force of 400 pN with 1 W Fiber Laser

-

Manipulation of Trapped Objects with Nanometer Precision

-

Compact and Ultrastable Modular System

-

Programmable LabView? Software Interface

-

Easy-to-use Force Calibration without Detector Alignment

-

Scope of Applications:

-

from Single Molecules to Living Cells

-

from Polymer Elasticity to Microfluidics

-

from Molecular Interactions to Nanopores

Optical Trapping and Force Measurement

Optical tweezers are used to trap and actively manipulate microscopic objects. They also offer a vast area of applications by measuring forces applied to trapped objects.

The Optical Trap

Microscopic objects - like individual nano- or microparticles, cells, cell compartments, single or clustered molecules - can be trapped securely inside the center of a strongly focused laser beam.

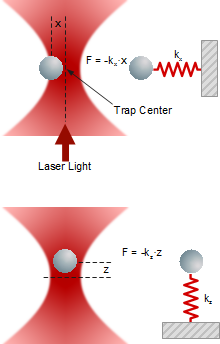

When an external forces is acting on the trapped object, it deflects from the center of the trap as the deflection x depends linearly on trap stiffness k and force F.

Lateral and axial forces acting on a trapped particle

Lateral and axial forces acting on a trapped particle

Forces

A trapped particle experiences various external forces. Atoms or molecules of the surrounding medium induce Brownian motion in all three dimensions, depending on temperature, viscosity and the presence of obstacles in the vicinity. Macroscopic fluid movements cause a drag force. Electric fields and bulk or surface charges may generate electrophoretic or electroosmotic forces.

Particularly, single molecules can induce forces of broad variety and magnitude while bound to the trapped object. On the other hand, the application of a force generated by an optical trap to a single molecule will gain vast insight into the molecular structure and elasticity, binding properties and kinetics.

Deflection is the Essence

Generating and metering various forces requires a reliable force measurement capability in all three dimensions to allow for a maximum degree of experimental freedom and versatility. Therefore, force detection is accomplished by precisely measuring the deflection of the trapped particle in each direction.

The PicoTweezers system utilizes a sophisticated and easy-to-use video analysis (right image below) for particle tracking, detection and force measurements. It offers the largest field of application since it clears common calibration difficulties, system instabilities, as well as experimental and spatial restrictions.

The evolution of force measurement. Left: Laser light passing trough the trapped particle (forward scattered light) is collected and projected onto a detector sensing the particle’s deflection. The condenser in close proximity to the trapping objective needs to be precisely adjusted. It is susceptible against drift and misalignment and limits the experimental space. Center: Backscattered light from the particle is collected by the trapping objective, separated from the incident laser light and projected onto the detector. This extremely robust setup allows high experimental freedom – the same applies for video-based detection method in the right image, where no detector alignment is required, too. In addition, a high diversity of trapped particles can be video-analyzed and measured.

The evolution of force measurement. Left: Laser light passing trough the trapped particle (forward scattered light) is collected and projected onto a detector sensing the particle’s deflection. The condenser in close proximity to the trapping objective needs to be precisely adjusted. It is susceptible against drift and misalignment and limits the experimental space. Center: Backscattered light from the particle is collected by the trapping objective, separated from the incident laser light and projected onto the detector. This extremely robust setup allows high experimental freedom – the same applies for video-based detection method in the right image, where no detector alignment is required, too. In addition, a high diversity of trapped particles can be video-analyzed and measured.

Video Detection and Analysis

Video-based force detection is easy to calibrate and provides an alignment-free and unsusceptible method for all force measurements in three dimensions. It is embedded into the LabView? platform.

The Principle

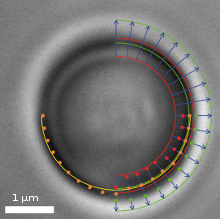

Video frame of a trapped microbead with various overlaid detection lines

Video frame of a trapped microbead with various overlaid detection lines

In addition to a video camera imaging the surrounding area of the optical trap, a second high-speed CMOS camera simultaneously surveys the magnified image of the trapped particle. The software searches for specific edges (as shown in the upper right quadrant of the image) in each frame and in real-time, determines gradients (lower right quadrant) and fits a circle (lower left quadrant) which correlates to the apparent particle diameter.

If an external axial force is acting on the particle, its apparent diameter changes, which the software translates into a z-force. Lateral forces only shift the center of the particle. These lateral deflections in the order of nanometers are then translated into x- and y-forces.

Easy and Reliable Force Calibration

LabView? based trapping, calibration and measurement software

LabView? based trapping, calibration and measurement software

Force calibration in three dimensions is conducted by moving the surrounding medium via the piezo stage using Stokes’ drag force law.

For specific applications, video-based force detection utilizes Allan Variance analysis and calibration. Here, smallest particle fluctuations are recorded and analyzed without the need of applying any frictional force. Both Stokes’ method and Allan Variance do not require the determination of the trap stiffness k, though the video-analysis software can calculate it if desired.

Benefits of Video-Based Force Detection

There is no need of detector alignment or adjustment in the beginning or during experimentation because the CMOS camera providing data for video detection and analysis is integrated into the optical pathway between laser and optical trap. Video detection is unsusceptible to disturbing particles that occasionally may be trapped together with the measured object. Since the diameter of the trapped object is permanently monitored, further particles of interest can be trapped and compared with previous ones. Specifically tailored Allan Variance for video analysis is a powerful calibration tool for experiments that take place in an environment that prevents other calibration or analysis methods. When trapping particles close to interfaces (bottom or ceiling of sample chamber, artificial or biological membranes, etc.), video analysis delivers an interference-free force signal.

Detection Tandem

Optionally, PicoTweezers can be equipped with additional backscattered light detection capability for simultaneous measurements or as stand-alone method, if experiments need to be conducted in absence of light or if particle fluctuations must be analyzed with highest sample rate in the kHz range.

Applications — Single Molecules and Polymer Elasticity

The elastic behavior of a single DNA-strand in absence or in presence of binding ligands can be reliably measured. Theoretical polymer models that are fitted to the results will deliver parameters, which characterize the polymer elasticity.

Grabbing a Single Molecule

A single DNA is immobilized between two microbeads.

A single DNA is immobilized between two microbeads.

To bind a single DNA-strand between two coated microbeads, it has to be properly functionalized on both ends. Thus, it can be immobilized between two beads, of which one is optically trapped and the other is held on the tip of a micropipette. Increasing the distance between the beads by moving the piezo stage induces a controlled mechanical tension to the DNA.

As a response, the force-extension curve of the molecule exhibit characteristic mechanical properties, such as an entropic elasticity, an overstretching plateau and a melting transition region.

Left: Force response of a single 48502 base pair long DNA molecule of bacteriophage lambda. In the force range up to 10 pN the entropic regime determines the elastic behavior of the molecule, whereas around 65 pN the characteristic overstretching transition occurs. The nature of this phenomena remains controversial, as well as for a less pronounced transition at 160 pN. Right: Fitting the Worm-like-chain model to the entropic regime yields two intrinsic elasticity parameters. For example, the persistence length strongly depends on salt concentration and on the presence of DNA-binding ligands.

Left: Force response of a single 48502 base pair long DNA molecule of bacteriophage lambda. In the force range up to 10 pN the entropic regime determines the elastic behavior of the molecule, whereas around 65 pN the characteristic overstretching transition occurs. The nature of this phenomena remains controversial, as well as for a less pronounced transition at 160 pN. Right: Fitting the Worm-like-chain model to the entropic regime yields two intrinsic elasticity parameters. For example, the persistence length strongly depends on salt concentration and on the presence of DNA-binding ligands.

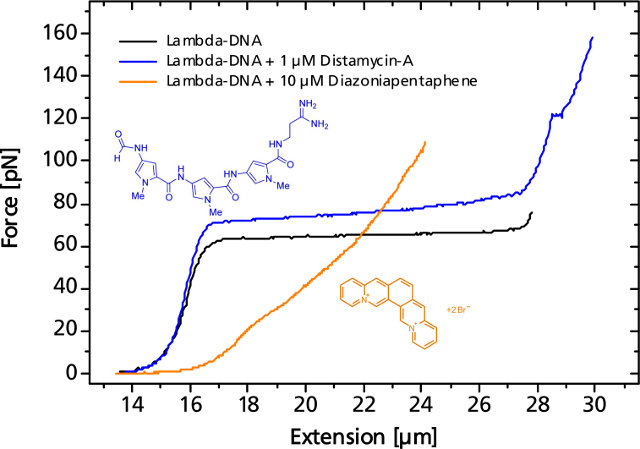

DNA as Sensor for Foreign Molecules

The DNA strand can serve as a host for a variety of different molecules, such as small intercalators, groove-binders, proteins, enzymes or molecular motors.

The binding event of a single or a multitude of ligands can change the elastic response more or less significantly. As an example, the force curve of a DNA is shown in presence of the antibiotic distamycin-A that attaches to the minor groove of the DNA strand while stabilizing it and helping to resist the overstretching. On the other hand, diazoniapentaphene as an intercalator increases both contour and persistence length and renders the overstretching plateau to disappear.

Small or large variations in the elastic response of a DNA-molecule in the presence of binding ligands can be measured.

Small or large variations in the elastic response of a DNA-molecule in the presence of binding ligands can be measured.

Applications — Translocation through Nanopores

Nanopores play a major role in biology and they rapidly evolved into a new and promising technique in single-molecule detection. The controlled threading of a single DNA molecule or a DNA-protein complex into a nanopore allows investigation of the translocation dynamics and a localization of the bound protein.

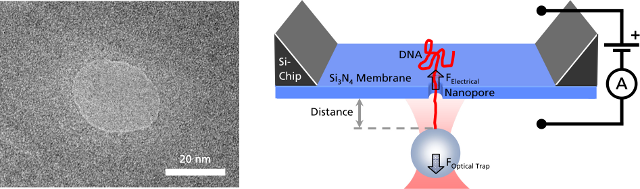

Left: TEM image of a solid-state nanopore drilled with a focused ion beam machine into a Si3N4membrane that serves as model system to study single molecule translocations. Right: Experimental setup of a DNA translocation measured with optical tweezers. When applying a voltage across the membrane, a single DNA molecule immobilized on a trapped microbead translocates through the pore. The electrostatic force acting on the molecule and the distance between bead and nanopore can be precisely measured.

Left: TEM image of a solid-state nanopore drilled with a focused ion beam machine into a Si3N4membrane that serves as model system to study single molecule translocations. Right: Experimental setup of a DNA translocation measured with optical tweezers. When applying a voltage across the membrane, a single DNA molecule immobilized on a trapped microbead translocates through the pore. The electrostatic force acting on the molecule and the distance between bead and nanopore can be precisely measured.

Translocating a Single DNA Strand

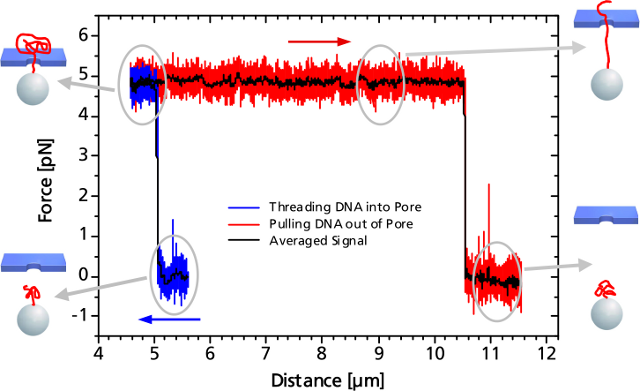

When the DNA on the trapped bead approaches the nanopore (to a distance of 5 μm) it is immediately threaded into the pore by electrostatic forces acting on the negatively charged DNA backbone. This effect can be monitored as an abrupt step of the force signal to a certain value, which remains constant even when retracting the bead. The measured force depends on the applied voltage, as well as on the diameter of the nanopore.

When the entire DNA strand with an end-end-distance of 10.5 μm is pulled out of the pore, the force drops back to zero.

Controlled DNA threading into a 55 nm solid-state nanopore with an applied voltage of 50 mV.

Controlled DNA threading into a 55 nm solid-state nanopore with an applied voltage of 50 mV.

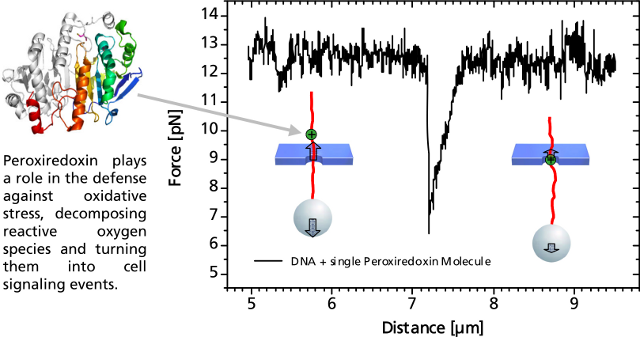

Single DNA-Bound Protein

A distinct asymmetric force signal occurs when a single peroxiredoxin molecule bound to the DNA stand is actively pulled through the pore. This effect serves as a label-free localization of the protein binding site.

It can be understand as the result of an effective positive charge of the protein counteracting the negative DNA backbone charge and reducing the electrostatic force.

Characteristic force signal of a single peroxiredoxin molecule bound to a DNA strand when both are translocated through a 35 nm nanopore.

Characteristic force signal of a single peroxiredoxin molecule bound to a DNA strand when both are translocated through a 35 nm nanopore.

We Design and Build Your Optical Tweezers.

PicoTweezers is a stand-alone system, that can also be customized to your Zeiss Axiovert, Axio Observer A1 or D1. It will be equipped with a 1 W or 5 W IR fiber laser for highest spatial trap stability yielding a trapping force of at least 400 pN or 2 nN, respectively.

The 3D-piezo stage enables nanometer resolution in a range of 200 μm in x and y, as well as 20 μm in z-direction. Video-analysis can achieve a lateral and axial resolution of at least 2.5 nm, which results in a force resolution of 0.1 pN with a frame rate of 200 and 400 Hz in z- and x,y-direction, respectively

References

-

S. Knust, A. Spiering, H. Vieker, A. Beyer, A. G?lzh?user, K. T?nsing, A. Sischka and D. Anselmetti

Video-Based and Interference-Free Axial Force Detection and Analysis for Optical Tweezers

Review of Scientific Instruments, 83, 103704 (2012)

-

A. Spiering, S. Getfert, A. Sischka, P. Reimann and D. Anselmetti

Nanopore Translocation Dynamics of a Single DNA-Bound Protein

Nano Letters, 11, 2978 (2011)

-

A. Sischka, A. Spiering, M. Khaksar, M. Laxa, J. K?nig, K.J. Dietz and D. Anselmetti

Dynamic Translocation of Ligand-Complexed DNA Through Solid-State Nanopores with Optical Tweezers

Journal of Physics - Condensed Matter, 22, 454121 (2010)

-

C. Kleimann, A. Sischka, A. Spiering, K. T?nsing, N. Sewald, U. Diedrichsen and D. Anselmetti

Binding Kinetics of Bisintercalator Triostin A with Optical Tweezers Force Mechanics

Biophysical Journal, 97, 2780 (2009)

-

D. Pla, A. Sischka, F. Albericio, M. Alvarez, X. Fernandez-Busquets and D. Anselmetti

Optical-Tweezers Study of Topoisomerase Inhibition

Small, 5, 1269 (2009)

-

A. Sischka, C. Kleimann, W. Hachmann, M.M. Sch?fer, I. Seuffert, K. T?nsing and D. Anselmetti

Single Beam Optical Tweezers Setup with Backscattered Light Detection for Three-Dimensional Measurements on DNA and Nanopores

Review of Scientific Instruments, 79, 063702 (2008)

-

D. Anselmetti, N. Hansmeier, J. Kalinowski, J. Martini, T. Merkle, R. Palmisano, R. Ros, K. Schmied, A. Sischka and K. T?nsing

Analysis of Subcellular Surface Structure, Function and Dynamics

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 387, 83 (2007)

-

A. Sischka, K. T?nsing, R. Eckel, S.D. Wilking, N. Sewald, R. Ros and D. Anselmetti

Molecular Mechanisms and Kinetics between DNA and DNA Binding Ligands

Biophysical Journal, 88, 404 (2005)

- 温馨提示:为规避购买风险,建议您在购买前务必确认供应商资质与产品质量。

- 免责申明:以上内容为注册会员自行发布,若信息的真实性、合法性存在争议,平台将会监督协助处理,欢迎举报